Research Practice: Organizing with Paper Notes

I've returned to one of my oldest yet tried and true research practices: sorting and organizing pieces of paper.

I've reached that point in the writing process where I need to start reorganizing, but also thinking about the logical structure of all the chapters. How do the chapters contribute to my larger overall argument? It's an important moment. On the one hand, I feel some relief to have largely completed the main part of the writing. But on the other hand, I'm concerned with how to connect the scaffolding. If each chapter is a wall and each section a brick, have I added up the pieces to support the entire home? Do all the parts really work together?

I'm surprising myself to find that it's easier at this point to print everything and work with the single sheets instead of writing on the computer. When I have the sheets in my hand, I can easily flip back and forth to review other pages, remove pages with bookmarks, and adjust it at other angles. As I work with the pages, I'm able to see my writing from new angles, write new comments on the side, and review the structure because I can review the chapters as if they are in a space around me.

Learning How to Take Notes

I used to work like this. And in some ways it's how I was taught to process and edit writing. I remember back in middle school, when I wrote my first research papers, we were taught to create physical notes and develop storyboards. Using a 3 x 5 index card, we wrote notes for the reading. Each note was supposed to be a "single topic" although we had to figure out how we defined "single topic". For instance, we decided if the note was going to be a direct quote from a source, a summary of a source passage, or an individual reflection in response to a reading or data point. To avoid plagiarism, my English and Science teachers (who both required us to use this method) encouraged us to use several visual clues (or reminders) on the note to distinguish which of the three classes our notes fell under. They were concerned that if we took direct quotes on the cards, but did not include direct quotes around it, and so thought that the quote was our own original work, we might later copy this passage and inadvertently commit plagiarism by directly copying somebody else's work.

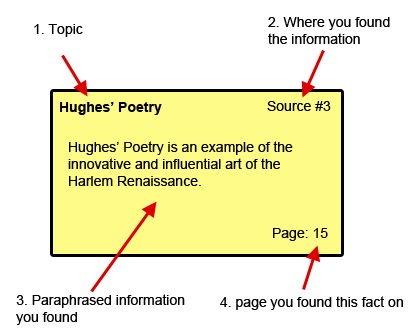

Notecard Example

This image from Gallaudet’s resources on researching is a similar example to the type of indexing system I was

Another check against direct copying though was the page number. After the initial note, you needed to add the page numbers or some kind of reference to the location where this passage came from. This was always helpful. The only case that it mattered less was if the notecard was a "thought-processing" card. Those were cards from the third category and maybe even extended into a fourth category. These cards represented creative thoughts and reflections about the general topic, but they were not necessarily derived from a specific source. They were self-reflective and argument building cards.

How To Use Headings

The most important part of the process though was the heading. Each note had to have some kind of label. The labels at the top were used to define how this note related to the questions we were asking in our research. So if the question were something like, "how did Babe Ruth shape mid-century baseball?", we would need to include some individual statement that clarified how that note about his batting average related to the topic. So in that example, I might have added "statistics" at the top of the card. It's not very descriptive, but it was an easy title which could be used to know that this card related to stats and the impact of say a batting average on the field. (These are purely manufactured examples, so I know die-hard baseball fans likely will have a clear answer that batting averages were not used as a measure until such and such a year. But I digress.)

Anyway, the second most important element in the heading was the citation and direction of the notecard. Each notecard was supposed to include a keyword that related it to the bibliography or source cards. Bibliography cards were an entirely separate deck of notecards. For every source that we encountered, we were supposed to create a bibliography card. The bibliography card contained all the relevant citation information: author, title, publisher, dates, edition. At the top of the bibliography card, we added another keyword for the short title. That keyword then was the word used in the reference card deck.

On the far left side of the notecard, we were supposed to add "directional" information on the card. That's my term. But I think its apt. When I was taught this method, they called it the outline component of the card. That is, we were supposed to add a short reference to our pre-writing outline. "IV.A.1". That kind of thing. Looking back, this was a mistake in the method. I was always confused why I had to add this, when I was aware that the outline would likely change. And it felt like I was committing to something too far in advance. That feeling was justified. I think we would have been better served to have added those annotations after we started the resorting process and started to write the first draft. Those kinds of notes would have been helpful as we re-processed the cards, not at the initial stage. And it's entirely possible that I misunderstood the process and was supposed to do it in this more iterative way. Except I could not ask anybody. I was homeschooled, so this was all done after I had completed the video lesson. I couldn't just ask for clarification from the teacher.

Not technically “research notes”, but the method has also been useful for constructing other kinds of outlines like I did while working on my exams and course outlining.

Using the Cards

Once we had the cards, we could then start sorting and mixing. The method encouraged us to "storyboard" our writing. We were supposed to lay out the cards on the floor and move our cards around and organize them into our emerging response. I always loved that part. By the time that I started to do this process I usually had around 200 cards or so. It was so helpful to sit down, read each card, and place it on the floor. It was like building a road map or a blueprint for the design. I could actually visualize how my thinking was changing as I decided to move one card from one place to another.

As previously mentioned, I was always confused at this stage though. Because I had added outlines to the cards, and at the time I was using a pen more than a graphite pencil for this, the note felt permanent not like something I could change as my thinking changed. This meant that it started to feel like there was some disconnect in this process to the way that my own thinking was morphing. The metamorphosis of the paper was not reflected in the type of storage here. (This is one of the reasons I later started to appreciate working with computers.) At the time though, I decided that I could probably switch to using pencils instead of pens as a more temporary solution. That meant that I could erase some of the headings and add new headings as I felt like the meaning of the notecard changed based on seeing the note card in context with so many other cards and references of information.

Note Cards in Context

When I started to attend high school, I discovered that I was the odd one when it came to taking notes like this. Most of my classmates thought this was an incredibly antiquated form of learning. Why was I using physical notecards when I could just make a Word document? Wasn't this the purpose of a research notebook? Wasn't this a waste of paper? And couldn't you lose all the cards? Taking notes in a Microsoft Doc was much more efficient and permanent. It was also easier to store and hold the individual note. There was no need to separate out individual notes and cards like this when a single document per source could become a note taking entry book.

They were half right. The technique is old, but I'm not convinced it's antiquated.

These past few weeks, I have been going back to this method. I've printed out several pages. And I have gone back to those old headings. I've started combing them again into a larger outline. This has helped me to visualize the argument, and it has allowed me to think differently about the goals of each section.

It's especially interesting to think about these practices in the context of some of my own research on inscription and graphical representation. I hope to write more about a couple of recent books that have helped put this into a new perspective: Markus Krajewski's Paper Machines and Matthew Eddy's Media and the Mind.

These are worthy of a review.